Ten Ways to Improve Bus Transit

This article is part of a series on simple measures how to improve urban transport. See also: Pedestrian Safety, Water Transit and Complete Streets

No matter how much sexier and livelier the debate about streetcars, light rail, subways or commuter trains is, the reality is that the majority of transit in the US happens on buses. Last year, buses were used nationwide for more than 5.35 billion "unlinked" trips (APTA report), which means bus trips account for half of all transit users and thus outdoes all other transit modes combined.

|

| Bus stop on Charles Street, Baltimore |

The most frequented mode of public transportation is also the most maligned, the least popular and the one with the biggest image problems. One could add to that list that it is the most poorly funded: With only between 23 and 27% of all transit investments the mode which transports more than half of all passenger gets only a quarter of the money.

One would think that there would be a rich body of policies and strategies on how to free the bus from this poor position, tons of ideas how to run bus service more effectively or how to measure customer satisfaction, and that the world would be full of agencies that race to implement the latest findings.

However, surprisingly this is not quite the case. Sure, there are is research and there are reports of the wonky National Transportation Research Board (NTRB) which once again will convene this week in DC. Also, there are enough agencies that have some type of service improvement program underway. Due to a lack of generally agreed upon performance metrics or customer satisfaction standards or national reporting, each agency seems to do their own thing and the bus remains the stepchild of public transportation, with just a few cities standing as exceptions.

|

| The bus route planning game includes cost, number of those serviced, layover and available streets (Source: MTA, Michael Walk) |

One bus initiative is happening right here in Baltimore, the Bus Network Improvement Project (BNIP), currently being undertaken by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), addressing the local bus system. In spite of its bulky name, BNIP started with a hip web-centric approach promising a quick succession of improvements but since has bogged down in the swamps of the bureaucracy. (See Phase 1 improvements of BNIP in this video). This appears to be a common fate. Almost all bus improvement projects I reviewed for this article are anything but simple. For starters they don't seem to be derived from a clear set of goals and objectives or even from a clear understanding of what problems should be solved with which priority. The transit systems in which the bus fleets are operated, maintained and put on the streets day after day are too complex, the hurdles that are put in the path of real change too cumbersome, the traditional ways of how things are done and have been done for decades too entrenched, and the ruts in which the bus transit discussion takes place too well worn.

By contrast, bus riders have a much simpler view on things. The frog perspective of the want-to-be riders that stands at the stop and peers down the street to see if the scheduled bus is really coming is probably the clearest view. The biggest complaints about buses are that they are unreliable and slow. Why can't buses show up on schedule, why do they come in bunches, why don't they show up at all sometimes, and why is it always a mystery when the bus will be there until it is in clearly view? Why do bus riders feel like cattle, under-appreciated and forgotten when they are clearly the backbone of transit service across the nation? The rider really wants three things: That the bus shows up ( reliability), that it gets to the destination in a reasonable time (speed) and thatgetting to the bus, the wait and the ride aren’t too cumbersome (convenience).

|

| Real time bus arrival signs in Portland, OR bus stop (photo Philipsen ArchPlan) |

To discuss improvements with more clarity it is worth to start with the rider's three generic metrics and not the operator's perspective. Of course, before considering remedies it helps to better understand why riders' expectations are disappointed every day in so many systems. Complexity sets in right away partly because the three rider metrics are clearly interconnected. A bus that is deadly slow will easily become unreliable and both of those characteristics are clearly inconvenient.

Unreliable and slow service can be caused by both internal and external causes. The external factors are those that are not the responsibility of the bus operators and their agencies such as increasing congestion in urban areas that makes all traffic slower, including buses. Then there is the creeping deteriorating of all infrastructure that not only leaves many city streets strewn with potholes, sunken manholes and warped asphalt putting extra wear on the fleet, but also leaves transit agencies underfunded for employing enough operators, maintaining the fleet or buying replacement buses. Lastly, there are political influences on every level of government down to an individual council person which make certain bus stops or routes untouchable, not to mention regulations such as Title VI (Civil Rights) or Maryland COMAR 7-506 or 7-208 requiring public hearings and 35% fair box recovery respectively, or rules about charter service (prohibited) or bus replacement schedules (ten years).

|

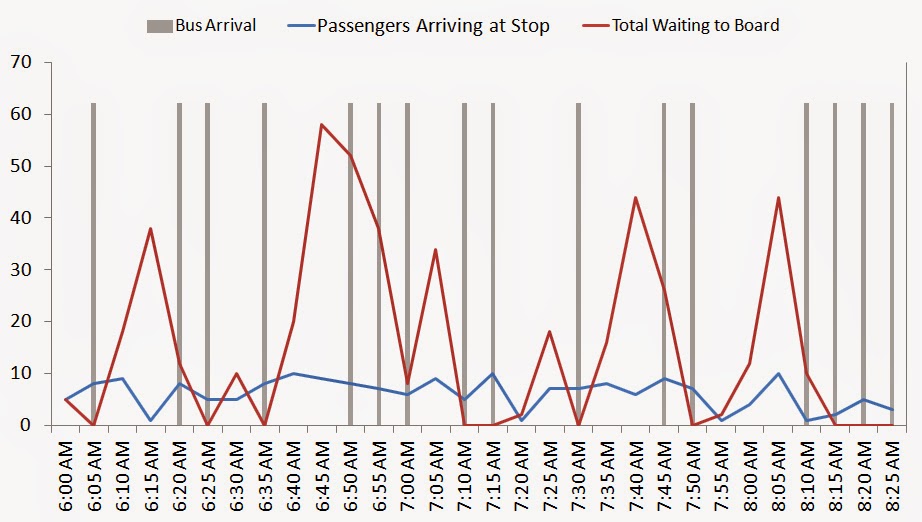

| Model graph illustrating how uneven headways such as delayed and bunched buses (the vertical lines) affect boardings at bus stops (red graph) and overcrowding of buses (Source: Michael Walk, MTA) |

But then there are a slew of internal reasons that vary from agency to agency, except for one core reason: Unlike private airlines, bus operations are monopolies without competition whether they are public or private. The lack of competition and their dependency on government procedures makes transit operations anything but nimble, slow in adopting new technology and slow in truly vetting their operations for efficiency. There is a tangle of rules, traditions, and bureaucratic nightmares regulating everything from operator breaks, to driver bathrooms, all items for which the public usually has little sympathy.

| Actual bus runs in a time-space diagram would show buses run in even parallel diagonals from stop to stop if they followed the regular headway schedule. However they distort due to heavy boarding delays which then exacerbate in a feedback loop to cause bus bunching |

Yet, there are bus companies that run their buses more efficiently, more reliably and more conveniently than others, who approached the bus service problem in a straight forward manner, namely Los Angeles. (The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) has become a leader in various transit initiatives ever after Antonio Villaraigosa became Mayor in 2005 and proceeded to turn LA from an auto dominated sprawl city into one with viable transit and concentrated growth including learning from Curitiba, Brazil). MTA began in 2005 to improve bus service with a simple set of goals, and clear metrics based on solid information about the then existing conditions, especially ridership per line, rider satisfaction, bus speeds per line and schedule adhesion.

|

| Branding and service types of LA bus transit (Source LA MTA) |

Next they set up two demonstration "rapid" lines up much like a scientific experiment, controlling for variables such as # and location of stops, route length, bus speed, signal priority etc. so that the effectiveness of each improvement could be measured against the baseline. The two demonstration lines were so successful on all counts that the Rapid Bus system has since grown into a full network of over 40 such bus lines. (For a detailed report see here). I learned all this when Baltimore considered just one rapid line service and I traveled to LA to research their system. The methodical LA approach allowed them to avoid most of the usual political hackling over where service has to be.

|

| The wonky way of studying bus service (Source: TRB conference. Photo: ArchPlan) |

The remarkable finding was, that giving the rider a faster, more convenient bus not only made it more reliable but also made the agency run buses more efficient as well. The MTA found that the initial Rapid Bus routes with their investment in branded buses, new stops, signal priority and a number of other improvements almost paid for themselves through increased efficiency and ridership.

The example of LA in particular shows a few principles with which to address the three rider goals of reliability, speed and convenience:

- Expand capacity for service through increased efficiency, not through more of the same. Transit providers who operate at the edge of their capacity in terms of vehicles or personnel need to create a margin so that small mishaps will not derail the service and ripple throughout the system and day. If in doubt, it is better to operate fewer lines or a slightly less frequent service and do it reliably rather than doing more and being overextended and vulnerable.

- Create a service hierarchy: Careful analysis of origins and destinations will allow the creation of priority trunk lines that become the backbone of reliable fast service. Those lines should be branded and be the ambassadors for the entire system by being extra reliable, fast and convenient.

Simple evaluation metrics for the LA Rapid Bus demonstration

(Source: LA MTA)

- Use increased speed as the magic bullet: If the service area is large and fixed and additional funds are hard to come by, capacity, efficiency and reliability can be increased by increasing the speed of the buses. This is the Southwest Airlines approach, which cut gate times by using a new boarding method and flying into less congested airports. That made them more reliable and efficient with more jets in the air than the competition. For buses that means three things:

- Cut long routes because they are more vulnerable than short ones. Shorter lines make operations easier to manage and more predictable. The disadvantage of more transfers is more than offset by the convenience of more reliable service.

- In collaboration with local government, attack external slow-downs like conflicting car traffic, signals, bad road surfaces and bad stop locations

- Accelerate the bus by eliminating overly frequent stops and long dwell times which slow buses more than anything else. Both of these causes the transit agency can control. The biggest contributor to long dwell times are cash payments at the fare box. Second is the number of stops and third their placement.

DC Metrobus latest vehicle

These three principles should be central to any improvement plan and once addressed, magic things like increased rider satisfaction and happiness will happen right away. Quicker buses will result in better fleet utilization, lower labor cost, more revenue and increased flexibility. Buses that save 10 to 25 percent of their running-time on a route will be back faster for the next service. No cash payments also will result in less cost for maintenance, vaults and cash management, potentially large savings. In short, a few things done right have a ripple effect that results in better service for less money, imagine that!

Taking all the above into consideration will finally allow a list of ten common sense steps towards better bus service addressing speed, reliability and convenience:

1. Break long routes into shorter pieces. Connect the route ends in transit hubs for easy transfer. (Reliability)

2. Get rid of cash payments in favor of collaboration with convenience stores that sell chip cards that can be loaded via cash or credit cards. There would still be farecard readers on the buses. Vancouver and Seattle want to do this in North America, London does it already in Europe. There is really no good reason why such a system couldn't be implemented in short order even in populations that have a strong cash economy. In the long run, with additional fare card readers, all-door boarding would allow even shorter dwell times. (Speed)

3. Eliminate about 25% of bus stops, especially in areas where stops are located in each block. The selection of stops to be eliminated needs to be based on public input and on boarding data. If the stop selection is based on a transparent set of metrics it is easier to defend eliminations and removes this topic from being a political football for local politicians and lobbyists. (Speed)

|

| Urban bus shelter with windscreen and seating Portland OR (ArchPlan) |

4. Negotiate with the local government about signal priority, queue jumpers and dedicated bus lanes in strategic areas. This, too should be based on clear metrics i.e. focused on areas where the other improvements still leave the bus travelling with a below average speed. It is easier to get those improvements in a few areas with a high return on investment than trying to make this happen as a general policy change. (Speed)

5. Implement an app for smart phones combined with a call-in service that allows real time bus information for each line and every stop. This isn't rocket science since most transit vehicles in the US are already equipped with GPS and transponders that emit the actual bus location. Knowing when the bus will actually arrive is possibly the biggest advance for riders even if it doesn't make the bus faster or more on time. But it gives riders certainty and allows users to manage their time avoiding unproductive excessive wait times. (Convenience)

6. Larger cities should tier their services into clearly differentiated and branded service types such as local bus, rapid bus, circulator or shuttle, and commuter bus. Within each type, simplicity should rule and the entire confusing thicket of variations be eliminated in which buses with the same line designation run as express or take different loops on the route depending on the time of day or their schedule time. The services on top of the hierarchy need to have the biggest ridership and run the fastest. (Convenience)

7. Clean and maintain buses well, and buy higher end models that are quieter, have a smooth ride and are fuel efficient. Recent model hybrid buses have finally caught up with the European Standard City bus in design and ride comfort, and most agencies have dispensed with dark tinted windows and unsightly advertising wraps. Good bus, good service equals better image and more riders. (Convenience)

8. Provide good information on paper, online, on the bus, and on the route about where buses go to and where transfers are located. (Convenience)

|

| LA Success (Source; LA MTA) |

9. Provide some basic amenities at bus stops. With fewer stops this will be less costly to do, especially when amenities such as shelters are sponsored by private industry. Generally, as the need for amenities decreases, the more reliable and predictable the service (Convenience).

10. Finally, a set of things not seen by the rider: Staff "back of house" operations with qualified people. Use clear quantifiable metrics to gauge progress. Provide impeccable customer service and allow riders immediate and simple feedback about each service. Use that feedback to steadily refine and improve the service. In spite of union rules try to implement performance bonus payments based on customer satisfaction.

As noted, implementation of even simple measures is not easy in the environment of public transportation. Not even mentioned here are complications that arise when transit agencies have to integrate bus service with light rail or subway systems in terms of schedule, ticketing and transit hubs. Still, one can assume that the principles would hold true and be successful. Bus as the workhorse of public transportation in America deserves all the attention it can get.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Edited by Ben Groff last updated 1/12/15 11:46

Related Articles on this Blog:

What it Takes to Provide a Bus Ride for 250,000 Riders a Day

What Makes a good Transit System?

What it Takes to Provide a Bus Ride for 250,000 Riders a Day

What Makes a good Transit System?

External Links:

Improving Transit Bus Speeds (TCRP Report 110)

Boston MBTA: Key Bus Lines improvements

Better Bus DC: WMATA Program

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment