With so many vacant houses, why is there still a housing crisis?

Why abandoned housing isn't affordable housing

By some estimates Baltimore has 40,000 abandoned vacant residential buildings, most of single family row homes. But like many other US cities, Baltimore also has a housing crisis, more specifically, an affordable housing crisis. There are as many people on a waiting list for what used to be called "section 8" vouchers. (Now "Housing Choice"). It is no surprise that many people think that there should be simple ways to reconcile those two numbers. Particularly in Baltimore, people remember fondly a 1970s program called the "Dollar House Program" and suggest that such a program could house the poor and get rid of the vacant houses at the same time.

None of this is limited to Baltimore. In fact, although the federal Department Housing and Urban Development (HUD) still has Dollar House program on the books, vacant houses are a persistent problem in many American cities and towns. Nationwide there are 12 million according to a report of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, especially in the "legacy cities" where population is stagnant or shrinking. This should serve as proof that solving housing problems isn't quite as simple as matching those who seek affordable housing and with abandoned housing stock.

An equal number of available "rooftops" and number of people looking for housing doesn't solve a problem even if defenders of a pure market economy would expect a big demand triggering a larger supply and expect some kind of balance to come about by itself. But even the largest demand and the slimmest profit margin doesn't change the basic fact that in market-rate housing, rent has to cover the cost. Where neither housing production cost nor income changes a lot, we find what economists call an "inelastic" market and large gaps. Gaps also arise from other factors:

The money problem

The economic argument , indeed, resides at the root of the housing crisis. To bring housing back into the range of affordability, it needs to be subsidized for a large group of people, immediately raising the issue of available subsidies. Clearly, there aren't enough subsidies to meet the needs, especially when it comes to extremely low income (ELI) households.

What fans of the Dollar House program forget is that even back when this program had its heyday in Baltimore, significant amounts of money were required to qualify for a 1$ house. Money that buyers had to prove they had when they committed to fixing the house up within a set period of time. Almost all of the 40,000 voucher seekers in Baltimore would not qualify. That they qualify for vouchers basically ensures that they don't have the capital for a major rehab job.

In order to solve the gap between needs and supply, extraordinary amounts of capital are needed, even if one accepts lower profit margins in affordable housing than in market rate housing. Location can be a real complication in dislodging capital. The bad location that makes the existing vacant house extremely cheap also makes it not marketable. Consequently it is near impossible to find individual investors to invest. Even people with very low income and a housing voucher would rightly not want to live in a neighborhood where the neighboring house is boarded, schools are terrible and crime is high. Forcing low income families into undesirable neighborhoods is now illegal and it is also counterproductive even though it was the basis of redlining, in which low income ethnic, especially black families, were barred from access to capital.

To remedy this sad history, the Baltimore Housing Department signed a consent degree with the Justice Department promising to avoid concentration of poverty. According to Seema Iyer, associate director of the Neighborhood Indicators Alliance of the University of Baltimore, vacant houses are the single strongest indicator of how well a neighborhood and its residents perform. Vacancies of 4% or more seem to deter people from moving into a neighborhood. Such reluctance then triggers further decline.

In short, the desire of reinvesting in communities that haven't seen any appreciation of properties in decades and the desire to accommodate poor people in areas of opportunity can be directly at odds with each other. Certainly, "the market" alone doesn't offer an acceptable solution to the housing crisis and does not bring decent, affordable housing of the right size, of the right quality into the right neighborhoods. All this requires subsidies and funds that are not only based on profit expectation and extraction plus large scale city wide planning.

In a time of decreasing federal largess (such as community block grants, the HOPE III and the HOPE VI programs and the like), states and cities are in the forefront of devising tools to come up with the needed cash. Their tools range from traditional, such as tax credits for affordable housing developers, to regulatory such as inclusionary zoning in which market rate housing has to come with a certain amount of affordable housing. Earlier this year mayors from 11 cities created a new non-profit housing coalition to coordinate affordable housing together.

The combination of market rate strategies and government regulation and funding is a hallmark of the "social democracies" of Europe who have a long tradition of filling the gaps between demand and supply in a generally market driven economy. Denmark, Germany and in particular Austria have bounty of attractive affordable housing models. It looks like those models will be re-invented and modified in the US.

The housing crisis and its consequences on health and social cohesion

The housing crisis in the US is real: The 2018 study, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes, by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) finds that there are just 35 affordable and available units for every 100 ELI renter households nationwide. Additionally 71% of ELI renter households are severely housing cost-burdened, spending more than half of their income on housing. HUD considers 30% as a reasonable limit for housing. Some economists question this particular 30% threshold because some other cost categories like food have come down a bit. Housing activists meanwhile argue that dispersal of poverty is only possible if vouchers

values increase in high rent areas. Regardless, tinkering with those definitions will only affect the margins of the fundamental problem, namely that income is too low, and housing cost is too high.

We already discussed some of the nuances of meeting supply and demand. In the emerging field of social determinants of health, housing has been identified as one of the biggest determinants for health outcomes. Consequently players in the field of health care begin paying attention to housing: Kaiser Permanente, for example, announced in May of this year, it will set aside $200 million to "impact investment" in affordable housing. In considering health, avoiding social isolation is an important factor that also could stand in direct conflict with the idea of dispersal of poverty. Jason Hackworth, a Toronto based planning and geography professor points to isolation as a risk factor in wrong headed urban renewal.

Solving the affordable housing crisis alongside with the crisis of blight of vacant properties is a dual task that isn't only needed for social cohesion and better health, it is also a necessity for cities to thrive economically. In addressing the complexity of the issue, many disciplines have to collaborate. In the desire to balance demand and supply in shrinking legacy cities, the simplistic approach of demolishing large swaths of abandoned housing units hardly solves the problem either. Jason Hackworth, the Toronto professor concludes in his paper titled "Demolition as Urban Policy in the American Rustbelt":

No city has ever demolished itself back to social, economical or fiscal health. San Francisco, Boston and Washington all were once plagued by abandonment and blight. They have largely filled their vacant housing stock and have done so much better than cities which currently focus on demolition, that it is easy to forget how far down on their heels those flagship cities had been as well. Now they have become symbols for the affordability crisis and economic displacement. As such they are just like their rustbelt brethren a case for the large capital needs for affordable housing.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

By some estimates Baltimore has 40,000 abandoned vacant residential buildings, most of single family row homes. But like many other US cities, Baltimore also has a housing crisis, more specifically, an affordable housing crisis. There are as many people on a waiting list for what used to be called "section 8" vouchers. (Now "Housing Choice"). It is no surprise that many people think that there should be simple ways to reconcile those two numbers. Particularly in Baltimore, people remember fondly a 1970s program called the "Dollar House Program" and suggest that such a program could house the poor and get rid of the vacant houses at the same time.

|

| Vacant houses in Baltimore (Vacants to Values) |

None of this is limited to Baltimore. In fact, although the federal Department Housing and Urban Development (HUD) still has Dollar House program on the books, vacant houses are a persistent problem in many American cities and towns. Nationwide there are 12 million according to a report of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, especially in the "legacy cities" where population is stagnant or shrinking. This should serve as proof that solving housing problems isn't quite as simple as matching those who seek affordable housing and with abandoned housing stock.

An equal number of available "rooftops" and number of people looking for housing doesn't solve a problem even if defenders of a pure market economy would expect a big demand triggering a larger supply and expect some kind of balance to come about by itself. But even the largest demand and the slimmest profit margin doesn't change the basic fact that in market-rate housing, rent has to cover the cost. Where neither housing production cost nor income changes a lot, we find what economists call an "inelastic" market and large gaps. Gaps also arise from other factors:

|

| Same houses getting renovated (Vacants to Value) |

- On the supply side price, location, unit size, home or apartment vary and serve different types of households. These factors tend to be reflected in cost, the factor with the greatest discrepancy between supply and demand. In other words, the right size home in the right location is no good if it is outside the range of affordability. And affordability even if following the definitions of HUD has a wide range based on area median income and housing cost burden.

- Conversely, an affordable home that is in the wrong location or of the wrong size is not much help either. The demographic mix of households looking for affordable housing is ever changing. Today more households are child free, consist of single adults or the elderly. New types of demand emerge, such as co-housing or live-work units.

- In the case of those vacant houses, they may cost very little to buy but they are not habitable, most of the time. To fix a rowhome up that has been vacant for years to make it habitable may actually cost more than building a new one. In an urban setting in a disinvested community even rowhouses that were occupied just a short while ago may have been stripped of copper pipes and other valuable components requiring costly repairs.

- Housing will not solve the problem even if fixed up, if it sits in deeply disinvested communities without educational or job opportunities and without basic services.

|

| Vacant properties in Baltimore |

The money problem

The economic argument , indeed, resides at the root of the housing crisis. To bring housing back into the range of affordability, it needs to be subsidized for a large group of people, immediately raising the issue of available subsidies. Clearly, there aren't enough subsidies to meet the needs, especially when it comes to extremely low income (ELI) households.

What fans of the Dollar House program forget is that even back when this program had its heyday in Baltimore, significant amounts of money were required to qualify for a 1$ house. Money that buyers had to prove they had when they committed to fixing the house up within a set period of time. Almost all of the 40,000 voucher seekers in Baltimore would not qualify. That they qualify for vouchers basically ensures that they don't have the capital for a major rehab job.

|

| Census tracts exceeding 10% vacancy rates, legacy city comparison: Leader is Gary with nearly 70%, bottom Milwaukee with less than 10% (Census data presented by Lincoln Institute) |

In order to solve the gap between needs and supply, extraordinary amounts of capital are needed, even if one accepts lower profit margins in affordable housing than in market rate housing. Location can be a real complication in dislodging capital. The bad location that makes the existing vacant house extremely cheap also makes it not marketable. Consequently it is near impossible to find individual investors to invest. Even people with very low income and a housing voucher would rightly not want to live in a neighborhood where the neighboring house is boarded, schools are terrible and crime is high. Forcing low income families into undesirable neighborhoods is now illegal and it is also counterproductive even though it was the basis of redlining, in which low income ethnic, especially black families, were barred from access to capital.

To remedy this sad history, the Baltimore Housing Department signed a consent degree with the Justice Department promising to avoid concentration of poverty. According to Seema Iyer, associate director of the Neighborhood Indicators Alliance of the University of Baltimore, vacant houses are the single strongest indicator of how well a neighborhood and its residents perform. Vacancies of 4% or more seem to deter people from moving into a neighborhood. Such reluctance then triggers further decline.

|

| Housing vacancy rates 1968-2016: Peaking during the Great Recession |

In short, the desire of reinvesting in communities that haven't seen any appreciation of properties in decades and the desire to accommodate poor people in areas of opportunity can be directly at odds with each other. Certainly, "the market" alone doesn't offer an acceptable solution to the housing crisis and does not bring decent, affordable housing of the right size, of the right quality into the right neighborhoods. All this requires subsidies and funds that are not only based on profit expectation and extraction plus large scale city wide planning.

|

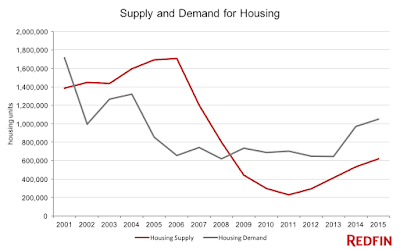

| Housing supply sits below of supply per Redfin in 2015, leading to recent boom in apartment buildings |

In a time of decreasing federal largess (such as community block grants, the HOPE III and the HOPE VI programs and the like), states and cities are in the forefront of devising tools to come up with the needed cash. Their tools range from traditional, such as tax credits for affordable housing developers, to regulatory such as inclusionary zoning in which market rate housing has to come with a certain amount of affordable housing. Earlier this year mayors from 11 cities created a new non-profit housing coalition to coordinate affordable housing together.

[..] current programs and federal funding are not meeting the demand, as one in four families that rent in our country are a paycheck away from homelessness, and families can no longer afford safe places to live. That is why local leaders need to develop partnerships with the Federal government, philanthropies, real estate and housing developers and other businesses to amplify the voices of struggling families and individuals, and to recognize that affordable housing is an investment in stable and thriving communities.(Website US Housing Investment.org)Recently, more and more cities come up with community reinvestment funds in which a city, town or county pools money from taxes, real estate transfers or other fees into a fund from which affordable units are funded. Baltimore just introduced a bill for such an affordable housing trust fund fueled by real estate transfer taxes that is supposed to yield up to $20 million a year. The bill heads for a hearing on September 27. Also recent is an effort of the private sector to step up its game in the difficult field of affordable housing and revitalization of disinvested communities. Jeff Bezos puts out a $2 billion fund to alleviate homelessness (no details are known yet) and private investment companies such as the Reinvestment Fund try to direct investors into risky areas by pooling funds and creating sound rehabilitation strategies. Baltimore's Barclay neighborhood is an example of successful investment into a community that was plagued by many vacant buildings and weedy lots. It was brought back to being a desirable neighborhood where now market investment is possible again. The effort successfully avoided displacement by maintaining many affordable units of different type and style, new and rehab.

|

| Demand and supply for various income brackets (NLIHC, 2015) |

The combination of market rate strategies and government regulation and funding is a hallmark of the "social democracies" of Europe who have a long tradition of filling the gaps between demand and supply in a generally market driven economy. Denmark, Germany and in particular Austria have bounty of attractive affordable housing models. It looks like those models will be re-invented and modified in the US.

The housing crisis and its consequences on health and social cohesion

The housing crisis in the US is real: The 2018 study, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes, by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) finds that there are just 35 affordable and available units for every 100 ELI renter households nationwide. Additionally 71% of ELI renter households are severely housing cost-burdened, spending more than half of their income on housing. HUD considers 30% as a reasonable limit for housing. Some economists question this particular 30% threshold because some other cost categories like food have come down a bit. Housing activists meanwhile argue that dispersal of poverty is only possible if vouchers

values increase in high rent areas. Regardless, tinkering with those definitions will only affect the margins of the fundamental problem, namely that income is too low, and housing cost is too high.

|

| Study by Lincoln Institute of Land Policy 2018 |

We already discussed some of the nuances of meeting supply and demand. In the emerging field of social determinants of health, housing has been identified as one of the biggest determinants for health outcomes. Consequently players in the field of health care begin paying attention to housing: Kaiser Permanente, for example, announced in May of this year, it will set aside $200 million to "impact investment" in affordable housing. In considering health, avoiding social isolation is an important factor that also could stand in direct conflict with the idea of dispersal of poverty. Jason Hackworth, a Toronto based planning and geography professor points to isolation as a risk factor in wrong headed urban renewal.

Solving the affordable housing crisis alongside with the crisis of blight of vacant properties is a dual task that isn't only needed for social cohesion and better health, it is also a necessity for cities to thrive economically. In addressing the complexity of the issue, many disciplines have to collaborate. In the desire to balance demand and supply in shrinking legacy cities, the simplistic approach of demolishing large swaths of abandoned housing units hardly solves the problem either. Jason Hackworth, the Toronto professor concludes in his paper titled "Demolition as Urban Policy in the American Rustbelt":

[..]the wider expansion of demolition as urban policy arguably aims to correct wider challenges. In a sense, it is a return to triage, but rather than using such logic to determine which neighborhoods can be saved with investment, it functions here as the extermination of the already-mortally-wounded neighborhoods. The notion, in short, that ad hoc, stand-alone demolition as urban policy is a means to market and community improvement is highly questionable. Its rationale is more plausibly explained as a way to improve conditions for economic growth elsewhere in the city.

|

| Households getting smaller means fewer people are needed to fill vacant properties |

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Comments

Post a Comment